In general, British policymakers, academics, and the public expect our forests to be managed for multi-functionality.

However, reconciling varied woodland uses is difficult for many land managers.

Only 13% of the UK’s land surface is wooded, thus conflicting woodland uses are often in close proximity to one another (UK Government, 2025)!

Therefore, many woodlands managers elect to manage for recreation, prioritising it over more “intrusive” land uses, such as commercial timber production.

Dudmaston Estate’s Comer Woods, Shropshire exemplifies both the virtues and pitfalls of this shift to recreation in forest management.

Comer Woods is a 185ha mixed woodland managed by the National Trust.

Being managed by the National Trust typically indicates that a site’s primary management priorities are recreational access, landscape quality, and conservation, rather than timber production (National Trust, 2023).

This is the case at Comer Woods, where although commercial tree species are present and intermittently harvested, timber production is a difficult topic for the National Trust to discuss with its members.

Within Comer, the trust takes care to ensure that timber is never allowed to take precedent over the recreational landscape. This makes sense, as the National Trust is primarily a conservation and access charity (National Trust, 2023).

However, where recreation is so highly prioritised, silvicultural knowledge may do little to inform implemented forestry practice.

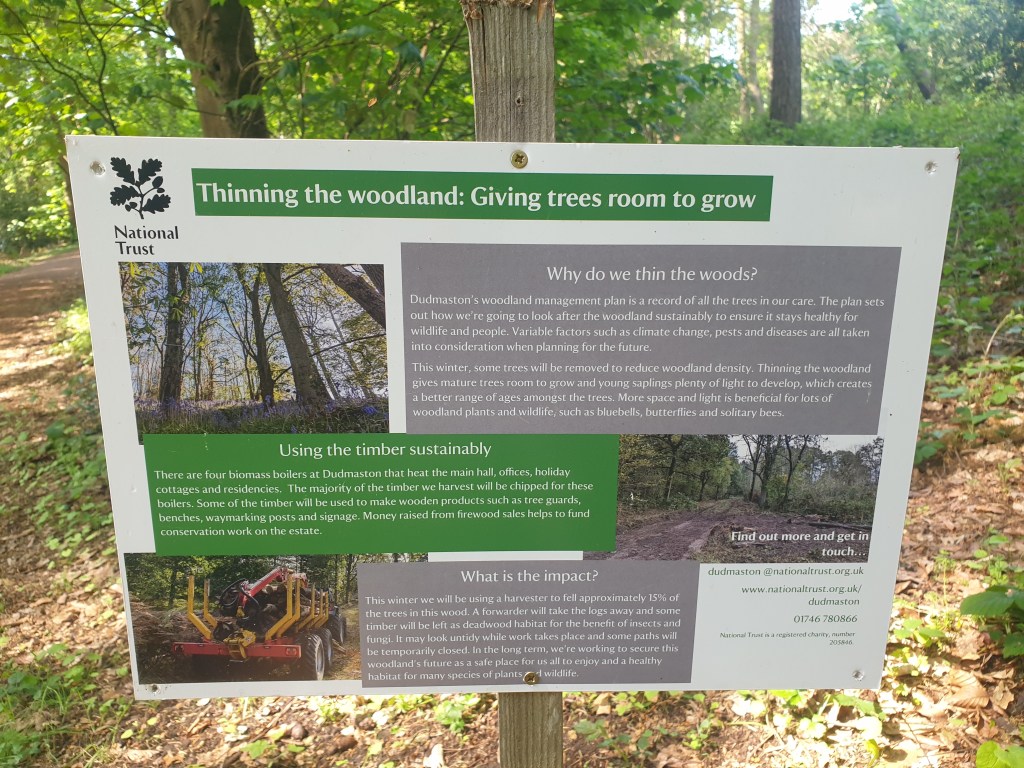

For example, at Comer Woods, the National Trust appeared concerned that even a conventional and ecologically beneficial thinning may be viewed as an infringement to the rights of fee-paying recreationalists.

The silvicultural intervention has evidently occurred in this case, despite recreational pressure.

But how many beneficial interventions never occur in woodlands like Comer simply due to the fear that the public wouldn’t understand and accept such changes?

How much biodiversity and timber productivity should be lost throughout woodlands for the sake of small-scale landscape sensitivity?

The need for signage to justify a conventional thin reveals both the primary virtue and the primary pitfall of recreation-oriented forests:

A recreationalist’s knowledge ecology, silviculture, or timber markets is irrelevant. Their opinion on how a forest should be managed is valid. This is not detracted from by any lacking in the mentioned fields.

Instead, the validity of a recreationalist’s opinion is determined by whether they paid for parking or not.

On the one hand, this phenomenon results in an increased managerial interest in public stakeholder engagement.

Increased interest in visitor preferences, as well as their health and well-being, is one of my favourite aspects of modern forest management, and it very much aligns with the UK’s national woodland policies (see WfW, England Trees Action Plan, Scotland’s Forestry Strategy).

On the other hand, dog-walking does not contribute quite as much to national security as a consistent domestic timber supply does.

Thus, it is important to remember what a multi-functional woodland actually is when they are advocated and managed for.

It is not simply a woodland that accommodates multiple forms of recreation (though I remain approving of walking, cycling, and horse tracks, of course)!

It is a woodland where both provisioning and non-provisioning functions are acknowledged, appreciated, and managed for, without an intrinsic ranking system of their “worthiness”.

Timber production is not an evil and unworthy usage of all woodland, and recreation is not a good sole usage of a purportedly “multi-functional” woodland.

If a manager is worried that woodland users will perceive these objectives to conflict, explanatory signage, as the National Trust has done at Comer, may be beneficial.

If most woodland users still percieve the objectives to conflict after this, then a fully multi-functional woodland is likely not appropriate in the given context.

The sooner a woodland manager acknowledges this reality, the better placed they are to deliver what the UK truly wants from her woodlands – purpose.

Thanks for reading.

– Bethany Breward

10/05/2025

References

National Trust. 2023. About the National Trust today. Available at: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/who-we-are/about-us/about-the-national-trust-today. Accessed 10th May 2025.

UK Government. 2025. Sustainable Development Goals – Indicator 15.1.1. Available at: https://sdgdata.gov.uk/15-1-1/#:~:text=The%20area%20of%20woodland%20in,and%209%25%20in%20Northern%20Ireland. Accessed 10th May 2025.

Links to policy documents

Woodlands for Wales: https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-06/woodlands-for-wales-strategy_0.pdf

England Trees Action Plan: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/england-trees-action-plan-2021-to-2024

Scotland’s Forestry Strategy: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-forestry-strategy-20192029/

Leave a comment