Today’s Forests in Theory is on charcoal.

If this topic seems somewhat dry to you, view this post as a form of immersive learning. In order to meet the FAO’s standards for charcoal, we must reduce the water content of this post to around 5- 15% of its gross weight (FAO, n.d.).

Charcoal is essentially a chunk of near-pure carbon formed by the removal of most of wood’s water content (specifically to 5- 15% of its gross weight).

This is done via pyrolysis. Wood is burned very slowly in a low-oxygen environment, such as an earth or metal kiln. Very high temperatures are reached this way, and very little smoke is produced.

The relative accessibility of its production means that charcoal has been a highly important commodity throughout history.

It was, and remains, an especially valuable commodity in densely populated urban areas, as it burns cleaner than un-pyrolysed wood (Mwampamba et al., 2013).

Charcoal could be considered as the impatient man’s alternative to coal ‘proper’, which must be mined, and requires millions of years of continued heat and pressure to form in the first place!

Conversely, charcoal can be sustainably produced at the rate at which wood grows. Better yet, you get the benefits of having trees in the meantime (though a forested land-use is obviously not viewed preferably in all scenarios).

Furthermore, the pyrolysis aspect of charcoal production may take less than a day, depending upon the method and scale of production (Bushcraft UK, 2019)!

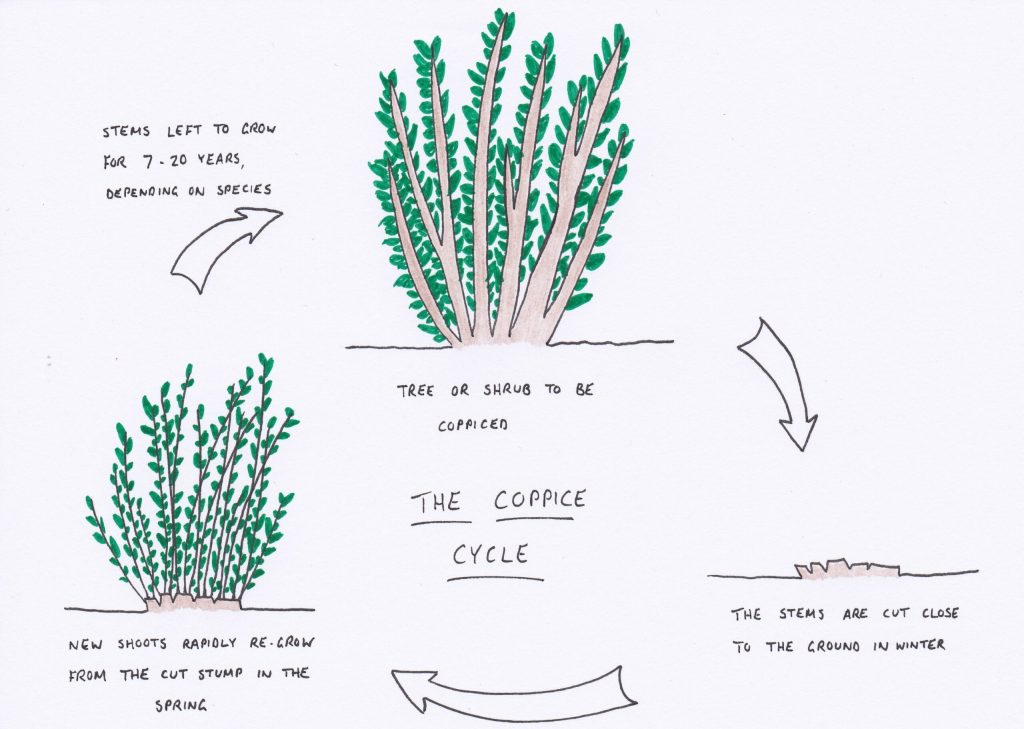

Coppicing is the traditional method of managing woodlands for charcoal production.

This is because coppicing produces large volumes of underwood in relatively short periods of time (that is, short for the forestry industry).

In an industry such as charcoal, where sizeable and high quality wood is not required, the usage of coppice and/or low quality wood material is ideal.

If you are unfamiliar with coppicing as a silvicultural intervention, it is further explained in this article.

So, could commercial charcoal production be the next get-rich-quick scheme?

Charcoal is certainly quicker than waiting for coal to form in your garden. However, “black gold” may be a misnomer for charcoal if referring to its UK-based production.

A relatively low demand for the product, paired with a high reliance on cheaper charcoal imports, means that the domestic charcoal industry in the UK is rather small.

In the UK, charcoal’s public image is primarily that of a useful BBQ fuel.

Furthermore, despite the UK’s relatively mild thirst for charcoal, demand is not met domestically. Instead, approximately 94% of UK charcoal is imported (National Coppice Federation, 2023).

The environmental impacts of this reliance on imports are not to be underestimated.

In addition to the general pollution associated with long distance trade, there is the more pressing issue that much of our imported charcoal is imported from high deforestation risk countries.

For example, in 2020 24,131 tonnes of charcoal imported into the UK originated from high deforestation risk countries (National Coppice Federation, 2023)!

Whilst the UK government regulates the import of most wood products to ensure that they were legally-produced, charcoal is currently exempted from such checks.

This means that charcoal export can be a lucrative vessel for shifting illegally produced wood, with charcoal being one of Europe’s top five drivers of global deforestation (National Coppice Federation, 2023).

It would be far too easy to villainise the charcoal itself.

However, charcoal remains a valued commodity, especially in developing countries.

Charcoal consumption is currently concentrated in African countries, due to its value as a transition fuel (Mwampamba et al., 2013).

‘This refers to the idea that charcoal provides “the energy that will sustain cooking needs of developing nations while other fuels are explored and their dissemination and adoption are more widely spread” (Mwampamba et al., 2013).

Furthermore, charcoal is important to the steel industry, where the development of more efficient pyrolysis techniques can result in lower-emission steel production than traditional fossil fuel methods (Kim et al., 2022).

Thus, calls to ban the global trade of charcoal altogether based on environmental grounds would be a highly disproportionate and misfounded counter to illegal deforestation.

For reading Britons, recommended action is to instead purchase FSC or PEFC certified charcoal, rather than uncertified charcoal. Even better, find out if you have any charcoal producers local to you!

For the more politically involved reader, the government as of yet does not regulate charcoal as a forestry risk commodity. This is despite the industry acting as a global driver of illegal deforestation.

Do with this information what you will.

Thanks for reading,

Bethany Breward, 11/07/2025

References

Adam. 2004. Traditional Earth Mound Kiln. [Photograph]. Available at: https://www.biocoal.org/earth-mound-kiln/. Accessed 10th July 2025.

Bushcraft UK. 2019. Charcoal making. [Online]. Available at: https://bushcraftuk.com/charcoal-making/. Accessed 10th July 2025.

Earthsight. 2017. Quebracho blanco from Paraguay’s Chaco forest ready to be fed into charcoal ovens before being transported to the capital Asuncion. [Photograph]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/andes-to-the-amazon/2017/sep/01/will-european-supermarkets-act-over-paraguay-forest-destruction. Accessed 10th July 2025.

FAO. n.d. Chapter 10 – Using charcoal efficiently. [Online]. Available at: https://www.fao.org/4/x5328e/x5328e0b.htm. Accessed 10th July 2025.

Hadley, G. 2022. The Coppice Cycle – a truly sustainable system. [Photograph]. Available at: https://ncfed.org.uk/public/coppicing/. Accessed 28th April 2025.

Kim, J., Sovacool, B.K., Bazilian, M., Griffiths, S., Lee, J., Yang, M. and Lee, J. 2022. Decarbonizing the iron and steel industry: A systematic review of sociotechnical systems, technological innovations, and policy options. Energy Research & Social Science. [E-journal]. 89(2214-6296), p.102565. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2022.102565. Accessed 10th July 2025.

Mwampamba, T.H., Ghilardi, A., Sander, K. and Chaix, K.J. 2013. Dispelling common misconceptions to improve attitudes and policy outlook on charcoal in developing countries. Energy for Sustainable Development. [E-journal]. 17(2), pp.75–85. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/charcoal. Accessed 10th July 2025.

Leave a comment